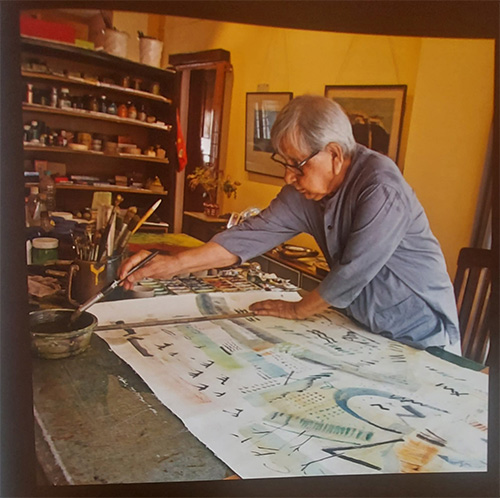

Ganesh Haloi turns 88 today. It's such a happy coincidence that I'm immersed in a book on him at the moment. I realized this morning that he is exactly my father's age (just a month apart). He has grown on me slowly, very slowly... ever since I translated an autobiographical essay of his a couple of years back (my only such tentative exercise till date).

Whenever I hear his name, I think of the teenaged aspirant applying at the Government College of Art and Craft (GCAC) Calcutta, with Howrah Station as his address. In the annals of the "struggles" of great artists, this surely must be one of the most harrowing examples. Haloi would later teach at the same institution where he had applied as a refugee boy, from 1963 up until his retirement in the 90s, becoming a beloved "mastermoshai" by then. I heard anecdotes of the teacher from an illustrious student of his last winter. The student is now a Professor at Kala Bhavan, where Haloi wanted to study but couldn’t. That didn’t stop the great artist-teachers of Santiniketan from becoming his “spiritual mentors”.

Between the studying and teaching at GCAC, Haloi spent seven years at Ajanta, being commissioned by the Archaeological Survey of India to copy the murals there. Those years would have a profound impact on his life and art -- just like his childhood in a lyrical landscape in Jamalpur, Mymensingh (in erstwhile East Bengal and East Pakistan) and his long refugee years surviving in disparate places in West Bengal and Bihar (from Ranaghat to Rajmahal, then on to Mokamay, and finally Calcutta).

At Ajanta, he not only copied murals meticulously but also explored the environment around, sketching the local landscape and labourers in daily toil. He would also sketch the street life of the city he made his home in the same decade; and later, his travels to other places of the country – to Rajasthan, Benares and Santiniketan. But he gradually shifted away from figurative and representational to abstract art – the ‘when’ and ‘why’ of which remaining unfathomable to his critics, beyond the fact that the transition happened over time and became his signature style. "He chose… to meander the paths of abstraction, where from his visual field, human figures were the first to recede and then gradually diminished recognizable objects from the everyday world around him”.

One of the most celebrated Indian artists of his generation, unlike many of his peers, however, recognition - especially at the national level - came to him late. A critic reviewing a group show of four contemporary Bengali artists in 1981 at the Jehangir Art Gallery, Bombay, had cited him as the “discovery of the show”. Though he lived through tumultuous times and stoically bore the scars of Partition lifelong, his career has been unmarked by any overt political affiliation; he remained “committed primarily to a continuous and intense engagement with his own practice.”

Haloi is represented by Gallery Akar Prakar. They regularly host shows on him; in fact, there is an India Art Far Parallel that is currently running in their Delhi Gallery, titled ‘Figure-ing Out’. I attended two shows of his at Akar Prakar Kolkata in 2022 – both memorable in their own ways. In one, the book I’m reading now was launched; in the other, on his scrolls, I briefly met him at the opening. I managed a ‘Namaskar’ and then ran away. I’m hoping I’ll have the opportunity - and gather up the courage - to speak properly with him some day.