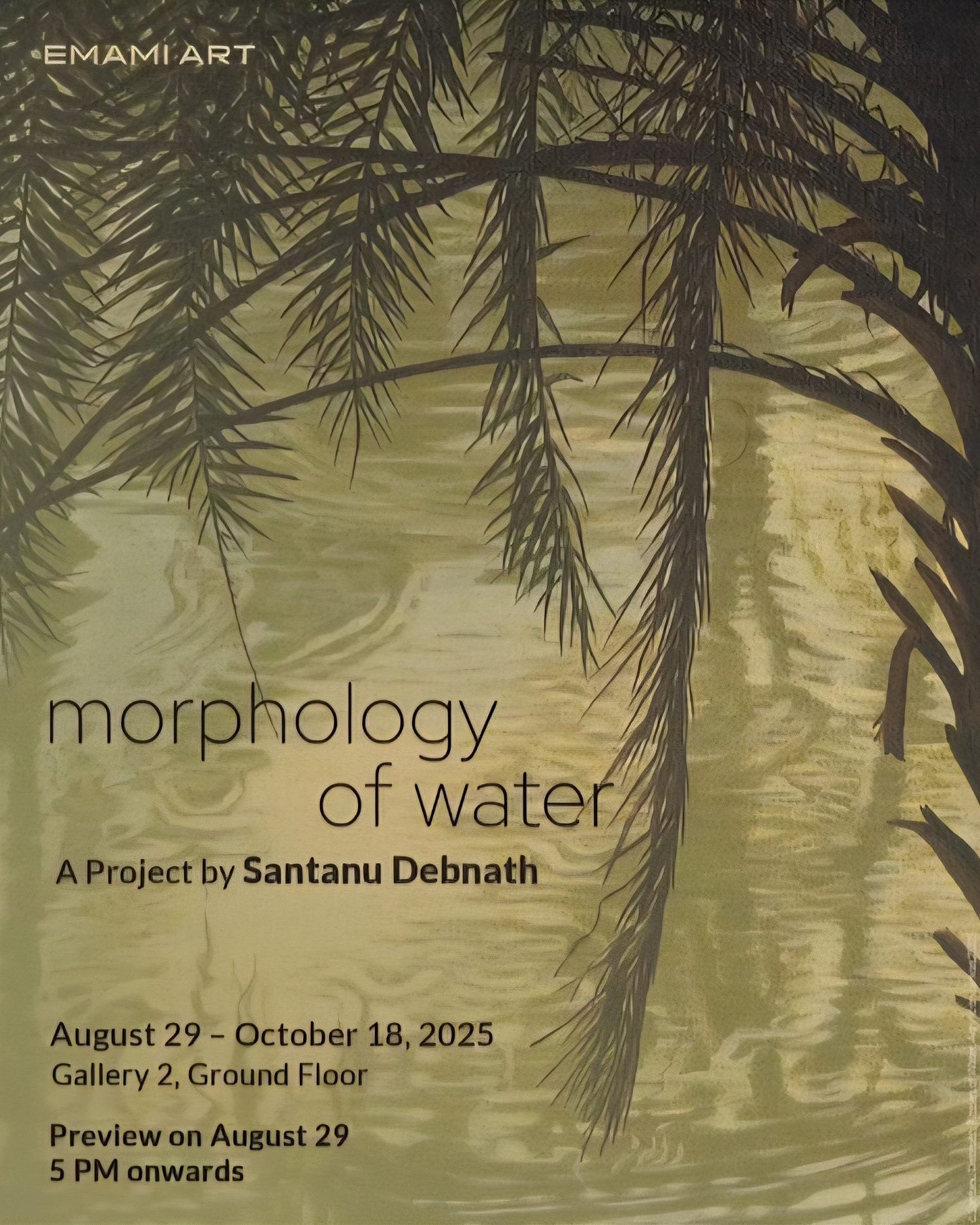

I frequently attend Exhibition openings at Emami Art and partake of the energy and excitement that they exude. But what I love more are the rare, quiet visits to the gallery on a weekday afternoon. One such was last Friday, at a time when I accidentally happened to be the sole visitor. The precious solitude it gave me (in what is usually a hyper-active space) couldn't have been more appropriate... since what I went to see was Santanu Debnath's MORPHOLOGY OF WATER. It's a solo that invites contemplation, a slowing down of pace, and stillness.

I'd first seen Santanu's work in a group show at Emami a couple of years back. It was a rural scene that stood out among the other exhibits of the show. His work again stood out for me, effortlessly, in 'LONGFORM: An Anthology of Graphic Narratives', where his contribution had no text. Titled ‘An Elegy’, it’s a stunning visualization of ecological erosion under the onslaught of urbanization. The same subject is revisited in the solo – but in a more intimate and detailed rendering, with a focus on aqueous landscapes.

The title of the Exhibition could well have been THE RETURN OF THE NATIVE. Because it was only after his return to his village, Betpukur (about 100 kms from Kolkata) – following the completion of his training at the Indian College of Arts and Draftsmanship and Government College of Art and Craft – that he began to see things differently, leading to the genesis of this body of work. Noticing the environmental changes all around, his attention was drawn particularly to the ponds and other water bodies that he found forlorn and neglected, in the absence of human company and human activities surrounding them, which were a given of his childhood.

He began drawing these aqueous bodies with meticulous precision – recording diurnal and seasonal changes in and around them with almost photographic realism. Two sets of 10 works – one, collectively titled ‘Ephemeral Reflections’ (acrylic on wood and iron nails); the other, with a separate title for each piece (all in acrylic on canvas); together with a set of 4, titled ‘Reflections of Seasonal Transformation’ – are the outcome of that studious exercise. ‘Daily Drawings’, another set of 10 works (graphite and watercolour on paper), and a pair of ‘Trembling Lilies’ are the other offerings. These are all small in scale. ‘A Memory Reservoir’ (acrylic on canvas) is the only large piece of work – giving us an expansive view of a long horizontal stretch of a lake.

'Ephemeral Reflections' is unique: painted on thin, oblong slices of wood, they are miniature reflections of every aspect of nature on water. Seeing these works, even while standing in a white cube space, one gets transported to Santanu’s village – such is their quiet power. The first thing that strikes one about them is the placid beauty of the scenes; many of the titles (in one of the sets mentioned above) lend themselves easily to this view: ‘Dawn’, ‘Dusk’, ‘Ripples of Water’, ‘Lush Green’, ‘Beneath the Tree Arch’, ‘Monsoon Lake’. A closer look, however, yields a different perspective – one then finds plastic bags, discarded bottles and other trash littering the edge of ponds and lakes, bearing testimony to environmental pollution. There are also a few exceptions, like 'Construction over Waterbodies', where the artist makes his point loud and clear.

The total absence of humans is another startling aspect of this body of work. Fish-nets in various forms that appear in several of the pieces - especially in ‘Ephemeral Reflections’ - are the only markers of human activity, but the humans themselves don’t feature in them. No women come to fetch water, no children play, nor men bathe in them. No huts or houses lie within their reach either; the water bodies are all far off from any settlement, there's not a hint of them anywhere. Even animals are rare; only a herd of buffaloes can be found immersed in a pond or two. But for them, Santanu’s Betpukur is a verdant but ghostly village.

Verdant is the operative adjective for the show. In studying the morphology of water, Santanu ends up exploring vegetal forms as much, or more. Imagine the vegetal richness and botanical accuracy of Millais’ ‘Ophelia’ multiplied manifold times! The result: every shade of the colour, at every time of the day, in the vicinity of every kind of water body is palpable here, turning the Exhibition space into a green haze.

I’ve had two personal experiences of such a phenomenon: once, while travelling by train from Heidelberg to Stuttgart at the height of a European summer, I mistakenly took the wrong train… and at one point, in that wrong direction, went through (what I can only describe as) a green tunnel – a few minutes of railroad whishing through trees on both sides. I can’t recall where this place was exactly, between which stations… but I remember those few minutes. And, for about a decade, I was used to walking under (what I love to call) a green canopy in Amsterdam – a tree-lined avenue, where the heads of trees seemed to touch each other as one looked up. Those few minutes and that decade left with me the same memory of a green haze. I was reminded of them while being lost in Betpukur.

But the green of Santanu’s village, however resplendent, does not signify what it is supposed to -- vibrant life. In his hands, it becomes the colour of mourning – the loss of a way of life, seemingly irretrievable. This is the most radical overturning of association there can be!